Chapter 8

The Town With Mean Eyes, Part 1

2 Thessalonians 3:13

But as for you, brothers and sisters, do not grow weary of doing good.

There was only one time in my life that I slept a more peaceful sleep than I did that night after the last meeting. I was content and smiled when I closed my eyes because I knew, just as sure as I laid my head on that feather pillow, that my family’s lives were full of a new hope and a new promise. Our lives were ours now, we believed that, and only God owned our souls. When I said my good night prayers that night it was with a new conviction. It was like we had all woke up to a brand new world. It was like we had all been reborn.

We looked at our days differently now because they were all for us. What we did, on each of those days, determined how well we made it in this county. If we didn’t do nothing we wouldn’t have nothing and this was a rough place, not to have nothing in it. We owed it to our boys and our past struggles to use our freedom to make something with our lives. Hilton and I made ourselves that promise. If the Lord was willing and there was a place where we could just have an opportunity to make it, we would take it.

I was putting on coffee that first morning of our new life and getting a breakfast ready for my men when I heard Jeremiah coming up the trail.

“Wooo. Woo, hoo. Mr. Hilton, Miss Elly. It’s me, Jeremiah. Miss Elly, sorry to come calling so early. Woo hoo, Mr. Hilton.”

The dark was still hiding in the lower parts of the tree branches and underbrush. A cool morning was just breaking on the farm. He must have woke the ferryman!

“I’m here,” Hilton answered. “By the woodpile.”

Jeremiah dipped his head down away from the house and the line he was walking and instantly looked back up towards Hilton. In one swift turn, he was quickly headed in his direction. He made a beeline straight for him. He was a bundle of excitement and it was funny, the way he walked right up to Hilton talking the whole time. It was like he was saying everything on his mind at the very same time he was thinking it. He would hold his arms out with his palms up like he was pleading one minute and then, the next minute, he would raise them up above his head like he was giving a hallelujah praise!

“Mr. Hilton, I got something I need to talk to you about,” he broke out with even before saying the first how do you do!

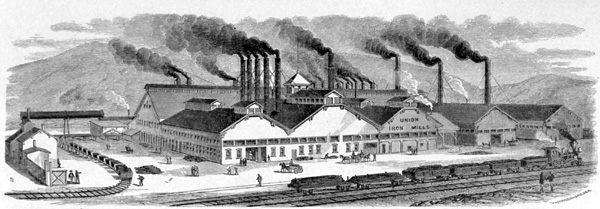

“I’m thinking about leaving the land between the rivers, Mr. Hilton but, before you say anything, hear me out. I’m thinking about moving to a real city, a big town, a place where everybody can have a chance. You know about that railroad they have going out of St. Louis, Mr. Hilton? Well, I aim to work at that iron mill just this side of the Mississippi River, in Illinois. It’s a big ol’ spur and there is a big demand for them rails. I ain’t afraid of hard work. If hard work is the only thing standing between me and a good living then you can count me gone. Watch out, boys! Whoo, doggie! Illinois is a free state, Mr. Hilton. Once I get through Kentucky I will be double free! A free man in a free state! Woo hoo, pappy!

I’m a free man now, Mr. Hilton. I’m a free man! I been up all night thinking about it. I feel like I been reborn again. I feel like my mama and my daddy lived and died for me to be free and now they done, somehow, seen me set free. I got to do right by them. I’m all they got left.

I know you been a free man a long time, Mr. Hilton. I know you already know what its like to be free. That’s why I come over here this morning, Mr. Hilton. To ask your advice. You see, I’m just new born free and I don’t want to mess it up. I don’t want to waste my freedom now that I just got it. I just don’t see no future for me here, Mr. Hilton. My mama is gone, my daddy is gone, and there is nothing holding me here. Besides, this land can be a hard and scary place if you are on your own. Not out here, not between the rivers. But what if I don’t want to always be a farmer? What if I just want to go into Town sometime? This County ain’t gonna change for a long time, Mr. Hilton.

Am I wrong, Mr. Hilton? Will I be messing up if I take my freedom papers and go to Illinois? They a free state! What does that mean, a free state?

How am I supposed to use this new freedom, Mr. Hilton?”

Jeremiah finally stopped talking. He was all talked out. He said everything that he had on his mind all night. No doubt he had not eaten. His eyes were full of stars and hope. I took coffee to the men as the biscuits baked.

Hilton looked like he tried to jump in and answer Jeremiah a couple of times, but Jeremiah kept firing his questions, one right after the other and didn’t give him the chance. Hilton just cocked back up on a stump smiling as he listened to his friend.

“You’re supposed to do just what you are doing right now, Jeremiah.” Hilton finally counseled. “You are supposed to ask questions. Will this be right for me? What are the consequences of my actions? First, you must convince yourself that you are free. Then you must ask yourself, how free can I be? How free do I want to be? It sounds like you want complete freedom. You won’t be happy with the kind of freedom they only ration out on Sundays. I don’t like that kind of freedom, either.”

Hilton had my attention now.

“I will say three things to you, Jeremiah, to answer your questions. First, never be afraid to try something new. You can always go back to where you were. Second, never knowingly move to a worse place or position than the one you presently occupy. Third, if I can talk Miss Elly into it, we’ll go with you!”

I nearly dropped my coffee.

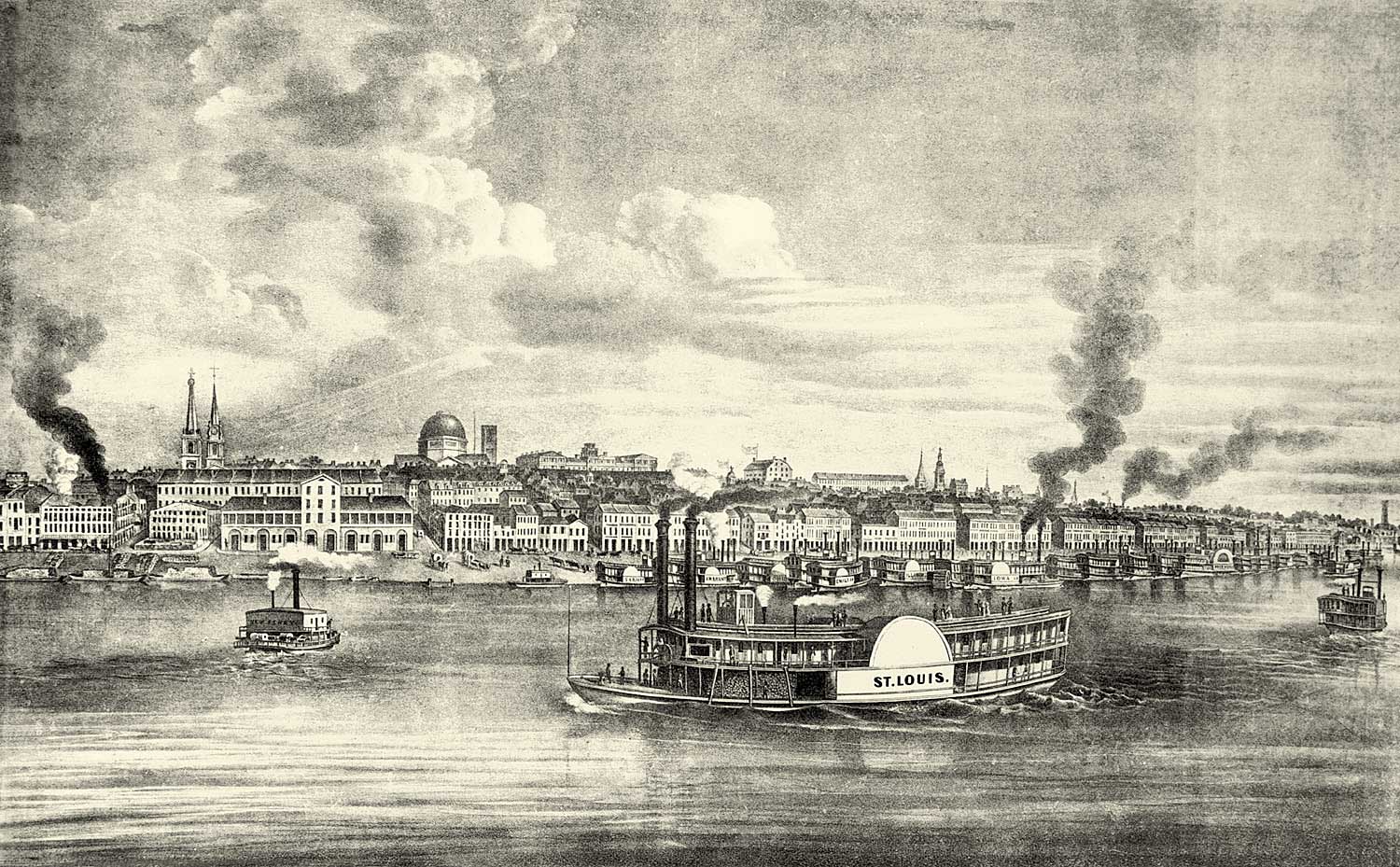

St. Lou, I repeated, when I came back to myself. The Lou lingered on my lips and the ooooh turned to aaah as I took a deep breath. It might as well have been Paris, France. It seemed so far away. Could the drawings in those river boat books be true? Could these wonderful places, these cities, exist? Were they there for us, too? What kind of amazing things would they have? Was it safe? Was it real? My head was so full of questions and excitement that I, suddenly, knew just how Jeremiah felt.

“Go with me, Mr. Hilton?” Jeremiah was surprised to hear that. “Really, Mr. Hilton?”

From way before he ever began planning to come out to the Great Western to work, Jeremiah always kept a strong desire inside himself to make a successful living. He was independent out of nature and he survived well his lot in life. He wanted to come over and make his mark at the Great Western. He was primed for it but she was gone now and nobody knew for how long. She was gone, but Jeremiah still had that fire inside him. He still had that drive for success. He knew in just under three days of travel that he could be through the backwoods of Kentucky, across the Ohio river, and up into Illinois. He knew he could catch a train from there that would take him to his iron and steel heaven.

“Those men are building that railroad spur going in twelve different directions,” he repeated to Hilton. “With your knowledge of iron and your organization of furnaces, with your contacts, we could easily land a job forming those rails. There is a future there, Mr. Hilton. Samuel and Hilmon can grow up free and educated sitting right alongside other free and educated children just like them. They would all be thinking free minded things and coming up with free minded answers at the same time. All of your friends would be free. There would be no more whipping and no more running from the dogs. Think of it, Mr. Hilton.”

“I have,” Hilton replied. “What do you think about St. Louis, Miss Elly?” Hilton asked me.

“It sounds exciting,” I answered. I was telling the truth.

Of course, I wanted to go to St. Louis! It was that magical place where we had been sending people to find their freedom. It was a place worth risking your life to see. It was another dream we were chasing and we seemed to be catching our dreams now. This was a dream that would be worth catching.

I was tired of the fight. Jeremiah was right. We could never win the fight here. Not in this county. The cards were stacked against us. Too much bias existed among the people and those in power chose to let it be that way. It was divisive, unfair, and non-productive but, that was how they wanted it. The powers that be needed the separation. They needed it to remind themselves that they were the superior ide. They didn’t care if some of the uppity folks left. They didn’t care if they had white trash or black trash on their hands.

Unfortunately, for the sake of the fair-minded, most of the time the bad people in Town outnumbered the good people in Town. You were on your own in a fix because the few good people in Town always had something to lose by standing up for what was fair. Everybody tended to keep their necks tucked in.

In some sense, it really didn’t seem like we were free. We were paper free, officially, but still treated as lower class. Here, we would always be talked down to. This was one of those places with that “Sunday morning” kind of freedom Hilton was talking about. I loved the country but, there was opportunity in the city. There was opportunity and real freedom.

Because of this and because of my children, I wanted to leave. Hilton spoke to Jeremiah.

“Jeremiah, we need to go, too. We need to go somewhere. I won’t raise my children to live with the madness and the evil that still lives here. We could go back to farming and make a decent living, as long as the weather cooperated. We could be free dirt farmers all day long and I might even set out a few grapevines. We could do all that. But I won’t. I want more than that for my children.

I won’t just up and move my family, either, Jeremiah. Not without a little bit of knowledge about where we are going. I propose you go ahead to St. Louis. You scout it out and I will give you the names of some of my contacts. You tell them what our plans are and see if they have a place for us. If there are jobs, find a safe place for us to live. If it is all so, Elly and I and the boys will join you. Maybe, as soon as the spring.

If money flows by red-hot iron in St. Louis then we will be a part of it. I see no reason to waste our talents here. For now, Elly and I will board up our farm at Cedar Pond and move back across the River to Saline Creek. We will squat over there and prepare for the journey to St. Louis. I believe you will find the industry you speak of, Jeremiah. I believe there is a place for us there. You go before us and we will follow in the spring. When will you leave and how are you set for money?”

“I will travel light and require little preparation. I leave Monday morning. I would leave tomorrow, but I have something to do. There is also something I would ask that you tend to until my return.

I have 75 dollars saved for the journey. It will be more than enough to get me there. I had 90 dollars saved. That was the twenty dollars I got for working each of the four years on the farm and the 10 dollar gold piece the Elams gave me. The only thing I spent money on was the 15 dollars for Mama’s funeral so I could bury her, proper. The burial was only 12 dollars, but I paid more to honor Mama’s last wishes. She said she hoped someday I could put a marker over her that read, “Daughter, Loving Mother, and Faithful Wife. My Darling Buck, until we meet again.”

Mama cried when she asked me if I could put a cross of white blossoms on her casket. She wanted the world to know, as they laid her down to rest, that she was a married woman. She was afraid to ask me. She was afraid for me worrying about it if I didn’t have the money. She just wanted a simple one, really, but I couldn’t leave it at that. I did make her one by my own hands and I put that one in her hands to carry with her. That way, my daddy can see it when they meet again, over Jordan. She was Mrs. Buck Porter and she wanted the world to know it. I paid the undertaker’s wife extra to make the one she had on her casket.

Just keep my Mama’s grave clear, please, until I return. If my daddy ever finds his way back here I want him to know that we all loved him.” Jeremiah had a tear fall down his cheek, but he quickly wiped it away.

The cross of white blossoms on Mrs. Buck Porter’s coffin was the biggest one anybody had ever seen. Everybody talked about how pretty it was and about how it was the mark of a married woman. His mama would have been proud.

“Jeremiah, I need you to have a fighting chance in St. Louis. 75 dollars will get you there but you need to survive and you need a way back if things don’t work out. Elly and I will give you another 75 dollars to help you out. Use the name of this contact first, he is a personal friend of Mr. Newell. If all works out you won’t need another.” Hilton wrote a name on a piece of paper and Jeremiah folded it up and put it with his money.

“I’ll send a letter back as soon as I get settled,” Jeremiah promised as he went back into his excited stage.

“Free, free, free! Oh, Lordy, me! What am I going to do, a free man up in old St. Lou!” Jeremiah was singing and bobbing his head around. Hilton was clapping his hands and slapping them on his thigh. Samuel was up by now with all of the bustling about and he was half stepping too, a little, in his sleep. A fishing pole was dragging behind him and dangling in his little hand. Everybody was laughing and happy and Hilton just swayed me around like we were dancing, too, but we wasn’t really dancing. We was just holding one another and it felt good, my man holding me like that.

I’ll never get over Jeremiah’s smile. He had been through so much in his short life but tomorrow was his new day to live and we all knew it.

“Right now, Mr. Jeremiah,” Hilton said, seriously, “You can help me stock that porch up with this wood. Winter is moving in fast. I can feel it in the air this morning. It will be a long time before we see another sunny day like yesterday.”

There was no time for crying now. That time had passed. It was only a time for rejoicing.

It was a good plan. Hilton felt like something was calling him away. He felt like we needed to leave this place and he wanted to be near that fire again. He loved the fire. He said when that iron was flowing red hot it was like holding a river of fire in your hands. Hilton Jacobs held a river of fire in his hands every day at the Great Western. Dover, even the land between the rivers, couldn’t hold him now.

Jeremiah ate four of my big ol’ cat head biscuits with red-eye gravy and two slices of ham, with eggs, before he left. I knew that boy had to be hungry. After being up all night, he was worn out by the time he went back across the river. He said he was going to clear his mama’s grave and then go home and rest up for the journey. He said he would pass back through on Monday morning. We knew it would be early. We would be ready for him.

Samuel and Hilton fished on the decision all day after Jeremiah left. My boys brought back a fine mess of fish to cook up. Hilton knew just the right time to be getting back home. He always made sure he made it with enough sunlight left to get the cooking done before it got dark. My job was to get that fire stirred up and my man could be counted on to be along just about the time it got to jumping.

Now, right on time, here they come and with a fat slab of creek steaks all filleted out and ready for the pan.

When everybody had a belly full and it got quiet, me and Hilton talked about St. Lou. We could send the boys to fine schools there, Hilton said. Life was easier in the big towns, he said. If you had enough money you didn’t have to do hardly anything. All the food you could ever eat was right there. Money was all it took. Hilton planned on having a lot of that. He said he would be very surprised if his contacts with Mr. Newell didn’t pan out. He said he thought we would be in St. Lou by the summer. Oh, Lordy me, I thought to myself.

After I accepted the fact that we would be leaving here for good, there were certain things about living between the rivers I would truly miss. I would miss the hummingbirds and the woodpeckers. I would miss the Cardinals and the Blue Jays. I knew there would be no eagles, no hawks and no owls in the city so I would miss them, too. I would miss the bull frogs and the lightning bugs. They were all around us. We lived with them. The yellow and black butterflies and bumble bees would flutter, fly, and buzz around us no more. The creek steaks would all be safe now from the sharp throw of Samuel’s well-trained lure. I sure would miss them. These animals knew nothing of the hurtful ways of man. They would live on in relative peace here yet, we would leave. I was ready to move on.

I really didn’t care what Hilton was saying. I was listening to him but all I knew was that as he was talking, his soft and strong fingers were rubbing the side of my head and my neck and my shoulders and it all felt so good. I hung my head and he rubbed my skull to the bone with an easy touch that soothed me. I closed my eyes and rolled my head back and let my shoulders fall so that my hands were limp, by my side. He rubbed the tightness right out of my arms and I felt the sweet touch of his lips on the back of my neck and my ears. Hilton said St. Louis and I said yes. He whispered soon and I said yes. He said when love is love, baby and I said yes, please baby, yes.

I slept the most peaceful sleep of my life that Saturday night. I believe Hilton did, too.

The boys didn’t fish on Sunday. We rested. Hilton read from the Bible and we sang hymns in the cool morning air. We thought about Jeremiah and about how he must be ready to bust with excitement.

Hilton had been up about fifteen minutes on Monday morning and had just enough time to get the coffee ready when we heard that woo hoo coming back down the trail. Jeremiah had woke the ferryman again! He said the happy boat tender would take no money from him for this trip across the river. He knew of Jeremiah’s travel to St. Louis and he wanted to send him away with good wishes. Jeremiah took this as a good sign. The ferryman was a friend, no matter how many times he woke him up early!

We said our goodbyes, for now, and we all believed we held the bright promise of a free tomorrow in our sights. I’ll see you again in the spring, Jeremiah said, as he backed away toward the North West trail. Even though he was a free man, he still had to get through Kentucky. Mose would go with him all the way to the Ohio River and see that Jeremiah’s boat returned from Illinois without him. We would then know, for sure, that Jeremiah was double free.

After Jeremiah and Mose passed through the trail we drank our morning coffee and imagined all the things we would see by this time, next year. Samuel woke up early and, imagine that, he wanted to go fishing!

“We’ve got to go to the “Blue Hole” today Mama! That’s a whole different kind of fishing.”

“Why is it different, Samuel?” I asked.

“They got BIG fish in the Blue Hole, Mama.” He held his hands as far apart as he could in describing those striped monsters.

“Samuel,” Hilton asked. Did you dig us up some big fishing worms last night?”

“I did, Daddy! I got us some good fishing worms. I even got us some half worms!”

Hilton smiled and laughed. “Some half worms? Did you get us any quarter sized worms, son?”

Samuel thought for a moment and answered, “No, but I can make you some.”

“That’s alright, son. We’ll make due.” Hilton looked at me when he spoke to Samuel. “You sure are one smart feller.”

“Mama says it’s because I take after her,” Samuel repeated what his Mama had said, many times.

Hilton looked back at me and smiled, “Your Mama is right and don’t you forget it.”

“I won’t, Daddy.”

I looked at Hilton. “You know why I tell him that, don’t you?” I asked. “Because I want him to grow up just like you. If I tell him he is just like me he will do everything in his power to be just like you. I believe he will have the best of both of us.”

Hilton smiled and nodded, yes. “Let’s go fishing, son.”

Ephesians 6:12

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the powers, against the world forces of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places.

“Jesus Christ, Opson!” Howard Claiborne screamed as he heard the news.

“Another five slaves escaped over the Sabbath? Where in the hell did they escape from? No doubt they were collected near the hollows of the Great Western and that bastard Luke Elam’s property.”

“No sir, Mr. Claiborne. These slaves were owned by the Bellwood Furnace and the Bear Spring Furnace. Three were from Bellwood and two from Bear Springs. They were caught by the dogs running in the woods off the trail toward Hopkinsville. They were on the other side of the river.”

“All slaves, Opson?” Claiborne inquired. Judge Virgil Kaney sat in the room with Howard Claiborne and Thomas Opson but did not speak.

“No sir, Howard,” Opson answered in a more cordial tone. The Bellwood slave had his family with him. Two slaves were from the Bear Spring Furnace.”

“Castrate the slave with a family, Opson and lock the two runaway slaves in the jail. We are putting a stop to all of this right now.” Claiborne knew he was the Judge, the Jury, and the Executioner. He was the god of his world. Who could stop him? Who could even stand up to him? His word was the law.

“The married slave is already dead, Howard.” Opson appeased. “The fool was shot trying to take up for his wife. The other two slaves are still alive. They’re half dead, but I’ll throw them in the jail if that’s what you want.”

“Opson, sit your arse down, boy, and listen to what I am telling you.”

Howard Claiborne was calling the shots. He cared nothing of anything that did not add to his wealth and power. More than that, he despised and loathed anything that threatened his throne. He would stamp it out. He had the power to do so. He owned it. Lives in the way did not matter. Human lives were counted in numbers to Howard Claiborne, not in feelings. Families were beneath him. Unity meant absolutely nothing to him. And this was how he treated the white families, the sharecroppers, beneath him.

Howard Claiborne was brought here, as a young child, by a military man on a land grant. That military man wasn’t his real father and word was that he worked the boy and his mother long and hard for a lot of years with little reward. It was told he treated them both real bad. Claiborne’s mother ended up dying too young. Most people said she worked herself to death. It wasn’t long after she passed that the military man just up and disappeared. Howard said he went hunting one day and never came back. That left the young Claiborne, at 17, to make it on his own. He never knew who his real daddy was and his mama was beaten down. That put a chip on his shoulder that he never got over. It turned him real mean.

Of course, this all happened long before the slave arrived. Howard Claiborne had dealt with “white trash” long before the negro landed in Stewart County. When Claiborne and all of his “progressive” Furnace owning friends found the slave they degenerated to a whole new level of superiority. They treated the negro as chattel, as real property. It disgusted them to believe that the negro could have the austere comeuppance to believe they could ever be free. And it wasn’t just poor white folk or black folk that Howard Claiborne treated badly. He made a habit of spitting on any Chinese man that walked by. He liked to make a spectacle of them to his friends and acquaintances. What could they do?

Many of those good people left this Town.

Howard Claiborne was an evil man. The sad thing? He was just one, of many. All of these Furnace owners arrived in Town and came into their own by various means. Whether it be inherited money, stolen money, or even hard earned money, it was all there. Murdered for money? Of course. It was there, too. This place didn’t get its rough name for nothing. And as for the money? The mean ones had the most of it. It was just the way of life.

Claiborne had lived long enough to see all of his partners, one by one, die. Cross Elam was the last to go. After Cross died Howard Claiborne saw himself as the last man standing. He believed it was left up to him to stop this creeping destruction of their empire. He must stop this escaping, this uprising. It was a rebellion against their old way of life. He would stop it, by God, he would.

“Boy,” he glared at Opson. “You’re going to earn your money tonight or I’ll have a new Constable by morning. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, Sir!” Opson sat up straight and listened with his eyes intent on what his owner was saying. He answered, smartly. The Major, himself, would have been proud of the military bearing his son displayed in answering so obediently. Opson was eager for his orders.

“I’m bringing in extra riders from Dickson and Ashland City, Opson. We’re going to take a team of men and go into every slave camp in this County. Go to every Furnace, Opson, and to every slave encampment. Burn down any church or worship area you may see. Bring me back the leader of each camp. We will stop this rebellion. We will stop this uprising now! Tomorrow is Wednesday, December 3rd. I want this over this week, Opson. Have all of the leaders of this uprising in my jail by Thursday morning. Do you understand me, Opson?”

“Yes, Sir!”

“Charge the camps with the extra horses,” Claiborne demanded. “The rebellion ends here. The next thing you know, slaves will be killing white people to escape. I am paying these extra men and horses for a reason, Opson. Charge the camps. Run over, with your horses, anyone that gets in your way. If they attempt to obstruct you, kill them on the spot! Do you hear me, boy?”

“Yes, Sir!”

“What did I say?”

“Kill them on the spot,” Opson repeated.

“Go to every camp. Run over anybody that gets in your way and burn something down, dammit! Bring me back the leaders. They will be the ones speaking out the most. Now, what part of any of that don’t you understand, boy?”

“I understand it all, Mr. Claiborne,” Opson assured.

“Meet the riders from out of town at the jail tomorrow morning and get to work, then.” Claiborne spit his sacred tobacco juice into the fire and wiped residue of it from the dried spot on his chin.

“And Opson, you take ten of those riders and go to the Great Western. I want Luke Elam and Hilton Jacobs in that jail tomorrow. Do you understand?”

“But the Great Western is shut down, Howard. They don’t even have a slave encampment.” Opson barely got his words out.

Howard Claiborne swung around and backhanded Thomas Opson right across his face and it knocked him out of his chair and onto the floor. Opson saw stars and didn’t jump right up and it was a good thing. Claiborne’s bodyguards were ready to finish what he started, but he waved them off.

Opson looked up at Howard Claiborne standing above him. “I said Elam and Jacobs, boy. You bring me Elam and Jacobs. Do you understand that?”

“Yes, Sir,” Opson answered.

“Catch them away from their homes. That way we can accuse them of anything. Now, if you want to keep that farm get the hell out of here and do your job.”

Opson disappeared into the night with his Deputies. There was no doubt that on the very next day, with reinforcements, their marching orders would be strictly carried out.

“You’re going to work Thursday too, Virgil. Get your robe ready.” Claiborne barked.

“What are we going to do with Luke Elam, Howard? You can’t just whip him like a negro.”

Virgil Kaney wasn’t completely without reason. While he was morally bankrupt, he wasn’t as insulated from the people as Howard Claiborne was. He didn’t have bodyguards or Committee of Safety members protecting his movements everywhere he went. He had to see Luke Elam in Town. He had to face his family on the square. He had to live with his decisions. He tried to do right in every other decision in the County that he could. That way, he rationalized, people would forgive him for always ruling in Howard Claiborne’s favor. He bent the rules a little and the money wasn’t bad.

“I’ll have him whipped harder than any negro you’ve ever seen! What the hell do you mean I can’t whip him?” Howard Claiborne snarled his lips and gritted his teeth. His snake eyes grew tight as they honed in on Virgil Kaney.

“Luke Elam is the worst of all white men. He is a white man with a conscience, a sense of righteousness. He is always talking about some kind of soulful truth that is supposed to, somehow, miraculously, set them all free. Ha! That’s a load of horse shat. Work hard and save your money, they say. Live by the straight and narrow, they preach. A wagon load of Christians never owned anything but a wagon load of faith and faith won’t pay the bills, Kaney. I didn’t get to this position by having a conscious, boy. Men like Luke Elam are a threat. Luke Elam costs me money. He takes money out of my pocket and he gives it to those lowly workers as if they meant something like their lives mean something. They don’t mean anything. Not in this Town. Not if I have anything to do with it. Luke Elam will be in your Court Thursday and you will sentence him to 100 lashes of the whip at the stocks in Town.”

Virgil Kaney jumped from his chair. “I won’t do it, Howard. That’s a death sentence! You know the negro boy died at 75 lashes. 100 lashes will kill him! I have to live in this Town, Howard. Give him 50 lashes, give him a year in the County jail, take his sacred tobacco but, for Christ’s sake Howard, we can’t kill him. It will never be forgotten.”

Virgil Kaney was pleading for his life and his peace, too. He only wanted to sell his neighbors out a little bit at a time. He didn’t want to kill them. It was well known that Virgil Kaney was in Howard Claiborne’s watch pocket, but that had worked well for him up until now. Up until now Virgil Kaney was, pretty much, well liked out in the County.

“100 lashes, boy. You’ll give him that Thursday or there will be a new Judge in Town by Friday. You will then load up your obnoxious wife and your pretty little girlfriend and be gone or you will be in eternity by Saturday. Do you completely understand me, boy?”

Virgil Kaney’s left eye twitched under the pressure but only for a second, or two.

“I understand,” he said. “100 lashes. I’ll have to add 1 year in the County jail so I can say I didn’t know the whipping would kill him.”

Howard Claiborne laughed.

Exodus 33:14

And He said, “My presence shall go with you, and I will give you rest.”

On December 3rd, 1856 I woke up earlier than usual. I could feel the cold of winter biting in the air. Hilton rousted himself out even before me. The first thing he did was poke and stoke up that fire and I was glad because it chased the nip right out of the air. I loved to pull the quilts up to my chin and stare at the sparklers and the sparkles of my man’s fire. Anywhere he made it, his fire was good. I could feel the heat and the warmth of it on my face. I felt safe so I closed my eyes for a few more minutes. When I woke back up Hilton was already outside. He was gathering up things down by one of the out buildings and putting them on a wagon.

I looked in on Samuel and little Hilmon before I mashed up a nice, warm sweet potato pudding for breakfast. I took Hilton some of it out by the wagon. He nearly had it loaded. We sat there like two children, without a care in the world, happily eating our warm milk and butter, sweet potato pudding and I asked him if we were taking all of this with us to St. Lou. I asked him about his plans for the day.

“We’ve got to do something with it,” he said. “Some of it will go with us. Most of it, we will give away once we get back across the river. If things work out, it will be a long time before we ever come back here. Our boys will be grown men, Lord Willing, and they may not want to come with us if we did. Although, Samuel could talk me into returning if he brings up all of the good fishing holes around here. I’m sure he’ll remember them.

Samuel and I will be leaving out earlier than usual this morning. We will fish one more day and then we will give you a break on fish, Mama. It wasn’t easy, but I’ve talked Samuel into a quail hunt for tomorrow.

Today, we are going across the river towards Saline Creek to meet up with Luke. I will share with him our plans to move back across the river and stay closer to the Creek through the winter. I will ask him to go with us to St. Louis and I will bribe him with some of your sweet potato pudding. If he likes it as much as your blackberry pie he might just ride in the wagon with us to St. Lou.”

“Oh, my goodness!” I wallowed. “I sure hope he doesn’t come.” I was putting on some airs. The both of you in old St. Lou? And a steel town, at that! Before it’s over you two will own that town. I just don’t know if I could stand it,” I sadly lamented as I put my forearm to my forehead. “It all sounds so highfalutin to me. The stress of it all, the fancy parties with the Governor!” I blew out a long, “Whew!”

Hilton grinned and asked me if I had everything I needed. He put his arms around me and asked me, again, “Are you sure, baby?”

I could feel all of my man next to me.

I wish I would have never let him go. I was supposed to make him stay close to the house.

“When Samuel finishes his pudding, we’ll head out.” It woke me from a daydream when I heard him say that. I was awestruck and I smiled. I just smiled and I let him go.

“We might be a little later than usual getting back, but not by much,” he finished.

“I’m ready, daddy!” Samuel shouted as he ran out the door. He was still wiping sweet potato pudding from his chin. “Where are we going today, daddy?”

“We’re going across the river to the Cave Spring fishing hole. The one by Kingin’s Hollow.”

“The supper hole, daddy?” Samuel’s eyes lit up when Hilton nodded yes.

“Mama, we are going to the supper hole today,” he said, excitedly. “You go there, you catch supper every time. It’s guaranteed!”

“Guaranteed,” Hilton repeated, as they walked away.

My men had been gone about an hour when I heard the horses coming. It was a big pack of them filling up the trail. They never did come on the farm. Instead, they kept going north, towards Kentucky. They had about enough time to get to the state line and back when I heard them again. They all rode back down towards the Great Western. This wasn’t normal and I knew something wasn’t right. We might, every now and then, see two or three riders policing the trail up to Kentucky, but there were at least a dozen, or more, of them now and they weren’t stopping for nothing. I was nervous for my boys and I wanted them to be home. I started the fire early.

It was just the normal time for them to be getting in when I heard the first news come back up through the trail. A former worker from the Great Western rode his horse fast up to the farm to tell Hilton what was happening. He told me, instead. The unknown riders had come out hard and heavy this morning, he explained. He said they went to every Furnace. There were so many of them, fifteen and twenty riders at a time swarming into every camp, setting fire to the altar churches, some homes, and even stomping on people with their horses. At Bellwood, he said, some twenty horses charged, shoulder to shoulder, up through a narrow trail that was rounded on it’s sides like a bowl. The people were all caught by surprise and were trying to run away but had nowhere to escape. It was like they were herding cattle up a chute. It all happened so fast, out of nowhere, and they couldn’t get away. Those newly deputized Committee of Safety Riders, led by some dark man, ran right over Hezekiah Tanner and the little grand baby he was trying to protect. Hez pitched the grand baby up the bank to safety just as that first horse trampled his legs and his hips. He would have been crippled for life if he had lived but, I swear, the witness said, that next rider aimed his horse’s iron shoes right for Hezekiah’s head. He found it, too, and Hezekiah was gone. Whenever they burned an altar, anybody who complained or even said anything was chained up and taken to the Dover Jail. They had six or seven slaves already locked up in there.

“Please come home, Hilton.” I whispered to myself and said a prayer to the Almighty.

Luke Elam met Hilton Jacobs by the Cave Spring pond and they let Samuel pick the spot to fish from. A cold spring flowed out of a deep and secluded cave and the pond it fed was already jumping with fish. They bit and nibbled on the poor and unfortunate bugs caught skimming along their surface. Luke was happy to see Hilton and he was happy to hear the news about us moving back across the river. He would open up the old Fitzhugh farm right next door to his property and Hilton and the boys and I would stay there, he insisted. The offer to go to St. Louis was very intriguing, Luke agreed. He said he would probably build another Furnace on Saline Creek, but all offers were on the table. He said he wasn’t looking forward to putting out a sacred tobacco crop this year without Jeremiah but, enough men had come back across the river from the Great Western to help and he could probably make it through one tough season. He laughed and added to Hilton, that was only if he didn’t take everybody with him to St. Lou.

“That Indian Cave is right there, Hilton.” Luke pointed to thick brush laying heavy on the side of a hill.

“I can’t even see the entrance, Luke. It’s covered up too good.” Hilton responded.

“I’ve been all through it and out all three exits and sometimes I still have a hard time finding it.”

“Daddy, look at this spot over here,” Samuel called.

“That is a fine place, Samuel,” Hilton and Luke agreed. The men followed the young man down the bank to the pond.

They had barely reached the water’s edge when Samuel let out loud, at once and without warning, a scared and frightened scream. Hilton and Luke jumped up in horror at what might be wrong as they heard the boy’s cry. It was a little boy’s anguished, high pitched tone and it had Hilton in an instant by his son’s side searching for the cause.

There, right before them, a man lay passed out on the ground. He was half in and half out of the pond and lay draped over an exposed tree root looking like he should be dead. He had only the shred of a shirt left on his body. His mostly bare back showed a mass of scars from the whip. His pants were barely hanging on his legs. They had been cut to pieces, no doubt, through countless miles of running and swimming to find his freedom.

“Samuel, stand over here,” Hilton said as he sized up the stranded man.

“We need to leave him alone,” Luke warned and he looked up and around for any sign of anyone else in the area. “Let’s get him up out of the water and see if he is alive but we need to get him out of sight before anyone sees us. He is clearly a runaway.”

The man was exhausted and cold and could barely crawl up out of the water. He explained he had been propped up on that tree sleeping since before nightfall. It was his first sleep in three days, he said.

“You are lucky,” Hilton said. “If those Committee riders had happened by here you would be easy pickings for them. They would have you in chains in a minute and taken back to where you came from. Where did you come from?” He asked the man.

“I’m running from a place named Tompkinsville, Kentucky,” the man explained.

“Well, you’re going the wrong way, fellow, if you are trying to escape. You are heading South and you are in Tennessee.” Luke revealed.

The men sat him up and dried him and gave him some sweet potato pudding to eat. It was all they had. They gave him another shirt to put on but could not replace his pants. As he gained his strength he began to talk.

“I’m not going north,” the man said. “I’m looking for a Town named Dover, Tennessee.” He splashed some water on his face and it cleared the mud away. “My name is Buck Porter and I’m looking for my wife and son, Jeremiah.”

As the mud was washed the man’s face became clearer.

“My Lord.” Luke mouthed the words, but they were barely audible.

Hilton just sat there, staring at him.

“What did you say, sir?” He had to make sure he heard that right.

“My name is Buck Porter,” the man repeated. “Four years ago a man named Cross Elam bought my wife and son off the blocks in that Dover town. He sent me north because I tried to protect them from his abuse. I didn’t like the way that old man looked at my family. I thought he was evil. I could tell he was a mean man. I didn’t want him to buy my family. I never dreamed he would split us up. It took me a year to figure out where I was up in Tompkinsville. It took another year to figure out where Dover, Tennessee was. This is my second escape. This is the second time I’ve tried to find Dover. They caught me once and swore if I ever ran again they would cut off my foot. They whipped me pretty hard for that. If I wasn’t such a hard worker that could go all day they would have killed me straight off. Am I close to Dover?”

“Daddy, he looks just like an old Jeremiah,” Samuel likened.

“Jeremiah looks just like a young Mr. Buck,” Hilton corrected his son.

“Buck Porter, welcome home,” Hilton said as he introduced himself.

“Mr. Porter, I want to tell you, your son is a free man. Jeremiah is a very smart and hard working young man and just this week he set out for St. Louis to work the steel mills to fashion those iron rails. We plan to join him in the spring. You must come home with us.”

“But what of my wife, Mr. Jacobs? Is my wife well?”

Samuel, Hilton, and Luke all looked, sadly, at the ground and Buck Porter knew the news wasn’t going to be good about his wife.

“She passed, Buck. I’m so sorry. She got the fever and died this past summer. I’ll take you to where she is buried. It’s in a pretty spot. Jeremiah stood strong for her, Buck, and helped her all through her sickness. You would have been real proud of your son, Buck.” Hilton tried to break the news easy, but there was no easy way to do it.

Buck Porter laid his head back on the ground and sobbed. He had no strength. His tears filled his eyes and four years of pain flowed down his face. He bowed his head and closed his eyes. He said a prayer for his beloved wife. He wished in his prayer for just one last time to tell her how much he loved her. He swore that he would have given his life for her. He apologized for making that man mad. He wanted to tell her he was sorry.

“Let’s go home, Buck. Hilton lifted his new friend off the ground. “We’ll tell you all about your fine son and what he has planned.”

Horses! Horses, all around the rim of the hollow.

“Stay right where you are, Luke Elam. You, too, Jacobs. Don’t either one of you make a move!” It was Thomas Opson come riding back on his stolen black stallion of death and he was yelling down into the hollow at the men.

The horses were on top of them so fast. No one saw where they came from and no one heard a sound, but they were all, with their hired riders, winding down through the hollow. They were closing in on them from every trail. They would be surrounded within seconds.

“Buck!” Luke screamed. “Take Samuel and get inside that cave before they see you. Go, now!”

Without thinking, Buck Porter grabbed up Samuel Jacobs and ran with him, in his arms, to behind the thick branches of foliage that hid the cave’s entrance from view. Luke directed them to the entrance. Although it was only ten paces from them, they both disappeared quickly into the cave just before the Committee riders got to the men.

“Where is that other man, Elam?” Opson demanded. “Where is that slave you were helping. I saw his ragged pants. He is a runaway. Where is he, Jacobs?”

“There was no one else, Opson. Just, us.” Luke Elam said.

“Liar!” Straddling high on his mean mount, Thomas Opson took the butt of his rifle stock and slammed it hard against the side of Luke Elam’s head. The elder Elam fell straight to the ground.

“Sit down, boy. Or I’ll kill you where you stand,” Opson ordered Hilton Jacobs as he was moving to help his fallen partner.

Buck Porter and Samuel Jacobs didn’t make a sound. The riders didn’t know of the cave and had no idea they were hiding only feet away from them. They looked everywhere for the man Opson said he saw, but he was nowhere to be found. No matter. Thomas Opson cared not to waste time quarrelling over a runaway. He had apprehended the men he was instructed to collect. He could go back to Dover now.

Opson directed the riders to tie the unconscious Luke Elam across a mule to be transported to the jail. Hilton Jacobs was handcuffed and put on the same mule. Opson and his riders led them both up the hollow and back across the river to Dover.

Samuel and Buck stayed in the cave until nightfall. The riders were long gone before Buck Porter would risk leaving the safety of the cave. Samuel told him he could get them home, even under the light of the moon. He said they would have to get to the ferry, but he could get them there, he was positive. After it got dark, Buck and Samuel listened. They listened for the sounds of a quiet night and anything different, anything unusual, even a slight crack or snap out of place in the woods, kept them longer in the darkness of the cave.

Finally, they made their way out into the night and towards the ferry. Buck was a little scared, but Samuel knew the ferryman, he assured. When they got there the ferryman knew of everything going on. He had crossed the river twice as many times as normal that day carrying all those damned riders back and forth, to and fro, and from one side of the river to the other. They never paid him. He ferried Luke and Hilton across as captives, earlier. The ferryman knew Hilton Jacobs was in the Dover Jail with Luke Elam. He was worried for Samuel when he didn’t see him with the Riders. He recognized, immediately, the little boy and he knew they needed help.

“Get over here, quickly,” He told Samuel and Buck as he hid them under canvas tarps covering some barrels on his ferry. He made the trip across the river as fast as he could, whispering to Buck and Samuel all the way.

“Be careful,” he said. “The riders are still out. They are mostly all drunk with whiskey now, but you must still be aware. Samuel knows the way home, but I will also tell you, it is about six miles from the bank of the river. Get off the trail if you hear anything. May God be with you, my friends.”

“Thank you,” an unbelieving Buck Porter said.

It was past midnight when Buck got Samuel home.

I started my cooking fire early that day. I kept it going a long time. It had been out for hours when I saw those two figures come walking back up the trail. I had been sitting on the porch rocking and rocking, just waiting for them, praying. I knew Samuel when I saw him. I could tell by the silhouette in the darkness that it was my little boy. I ran to them both like it was Hilton, too but, when I got to them I didn’t know who that man was bringing my boy home. Samuel was trying to explain, but it was all coming out of him at once. I was holding him and hugging and kissing him and trying to hear where my man was.

“I’m Buck Porter, ma’am. I came back here looking for my family and your husband found me this morning. Some Deputies came up on us and knocked out the white man that was with your husband. They knocked him unconscious and took them both to the Dover Jail, I heard them say. I’m sorry, ma’am.”

“Thank you, Buck Porter, for seeing my boy home. Let’s get inside and quiet. Tomorrow, we’ll go to Dover to see about Hilton and Luke.”

RLB4

This chapter will come in installments (sorry). It was either that or make those interested in reading more, wait. I will work hard, I promise to get the next installment of this chapter out. Installments of this chapter? Maybe, 2 more. Because of this episodic release, I will not put it out on Facebook until the chapter is complete. This is our secret. Thanks!

It took me awhile in between things I had to do, but boy oh boy …lol…sitting on the edge of my seat almost feeling their fear and pain and then …..BOOM…..I had read all that was there…..fantastic and I can’t wait to read the rest. So well done my friend!

Thank you, Bonnie! It’s really winding out now. After Chapter 8 is finally complete we go back to the beginning of this book, to the trial.

Chapter 8 Part 3 is a monster in its own right and I am working on it now.

Thank you again for liking it!

Robin

Нужно собрать информацию о человеке ? Наш сервис поможет детальный отчет мгновенно.

Используйте уникальные алгоритмы для анализа цифровых следов в соцсетях .

Узнайте место работы или интересы через систему мониторинга с гарантией точности .

глаз бога программа для поиска людей бесплатно

Система функционирует с соблюдением GDPR, используя только открытые данные .

Закажите расширенный отчет с историей аккаунтов и графиками активности .

Доверьтесь надежному помощнику для digital-расследований — результаты вас удивят !